The Russian for

animate noun is одушевлённое существительное. The word одушевлённое literally means ‘ensouled’, but it’s not that simple (of course!).

Animacy is a grammatical category consisting (mostly) of living things. However, some things that are not alive are nonetheless animate, and plants, though alive, are not animate. Collective nouns, even referring to groups of people, are not animate.

It is most noticeable (or applicable) to grammatically masculine nouns. It also applies to feminine and neuter nouns, but only a handful of neuters, and only in plural for feminines.

An animacy Venn diagram: a = animate, b = inanimate, and c may be either:

Some nouns that are unexpectedly animate:

- some words for dead people: покойник and мертвец (dead man) are animate, while труп (corpse) is inanimate

- the word лицо when meaning “individual” (but not “face”, its main meaning)

- things appearing human, such as робот (robot), чудовище (monster) пугало (scarecrow), снеговик (snowman)

- games, such as

куклы (dolls)

- court cards, like туз (ace) and валет (jack)

- chess pieces, like ферзь (queen [vizier]) and слон (bishop [elephant])

Things that may or may not be animate:

- little living things, like микроб (microbe), личинка (maggot), бактерия (bacterium), зародыш (fetus), эмбрион (embryo); this is dependent on the speaker's attitude.

- non-mammals that are eaten, like устрицы (oysters) or креветки (shrimp), are animate if being talked about as animals but inanimate if being talked about as food.

Now: the $64,000 question: Why does this even exist? There's actually a very good semantic reason behind it.

Because Russian word order lets the direct object be in front of the verb and the subject behind it, sentences such as “man bites dog” would be ambiguous if there were not a grammatical way to tell the cases apart. Animacy is that way.

Since masculine accusative has the same ending as nominative, masculine and neuter animate nouns take the same ending as genitive in the accusative. This allows for the subject and object to be clearly marked. Inanimate nouns generally can't be confused for the subject - a cat may look at a king, but a table cannot. Feminine nouns, of course, already have a different accusative ending.

Some examples:

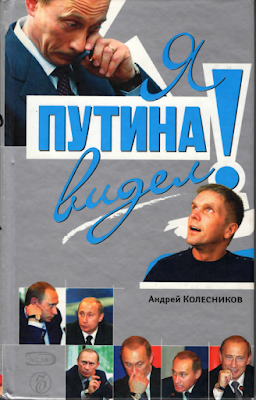

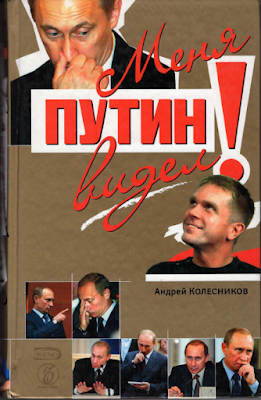

- Человек видит кота = the person sees a cat

- Кота видит человек = the person sees a cat

- Человека видит кот = the cat sees a person

- Кот видит человека = the cat sees a person

Compare:

Стол видит человек = the person sees a table

With neuter:

- Человек видит чудовища = the person sees a monster

- Чудовища видит человек = the person sees a monster

- Человека видит чудовище = the monster sees a person

- Чудовище видит человека = the monster sees a person

Compare:

Окно видит человек = the person sees a window

Things are more straightforward with feminine nouns, as they generally have the У ending in accusative, which is different from both nominative

and genitive.

Женщина видит книгу = the woman sees a book

However, when both subject and object are feminine nouns in –Ь, there is ambiguity. Who loves whom in this sentence: Мать любит дочь? Here (and only here) does Russian rigidly adhere to SVO word order:

the mother loves the daughter, and never the other way around.

But what if you want to reverse the word order? You'd think they'd use genitive endings, but they don't. In fact, this is a good sign that nothing is "planned" in language. Instead, the workaround is to use a modifier, which shows the case endings:

- Свою мать любит дочь

- Мать любит свою дочь

And since the rule is use the genitive endings for accusative when the accusative and nominative endings are the same, leading to confusion over who is acting and who is not,

for animate nouns in all genders – including feminine – the genitive endings are used for accusative in the plural.